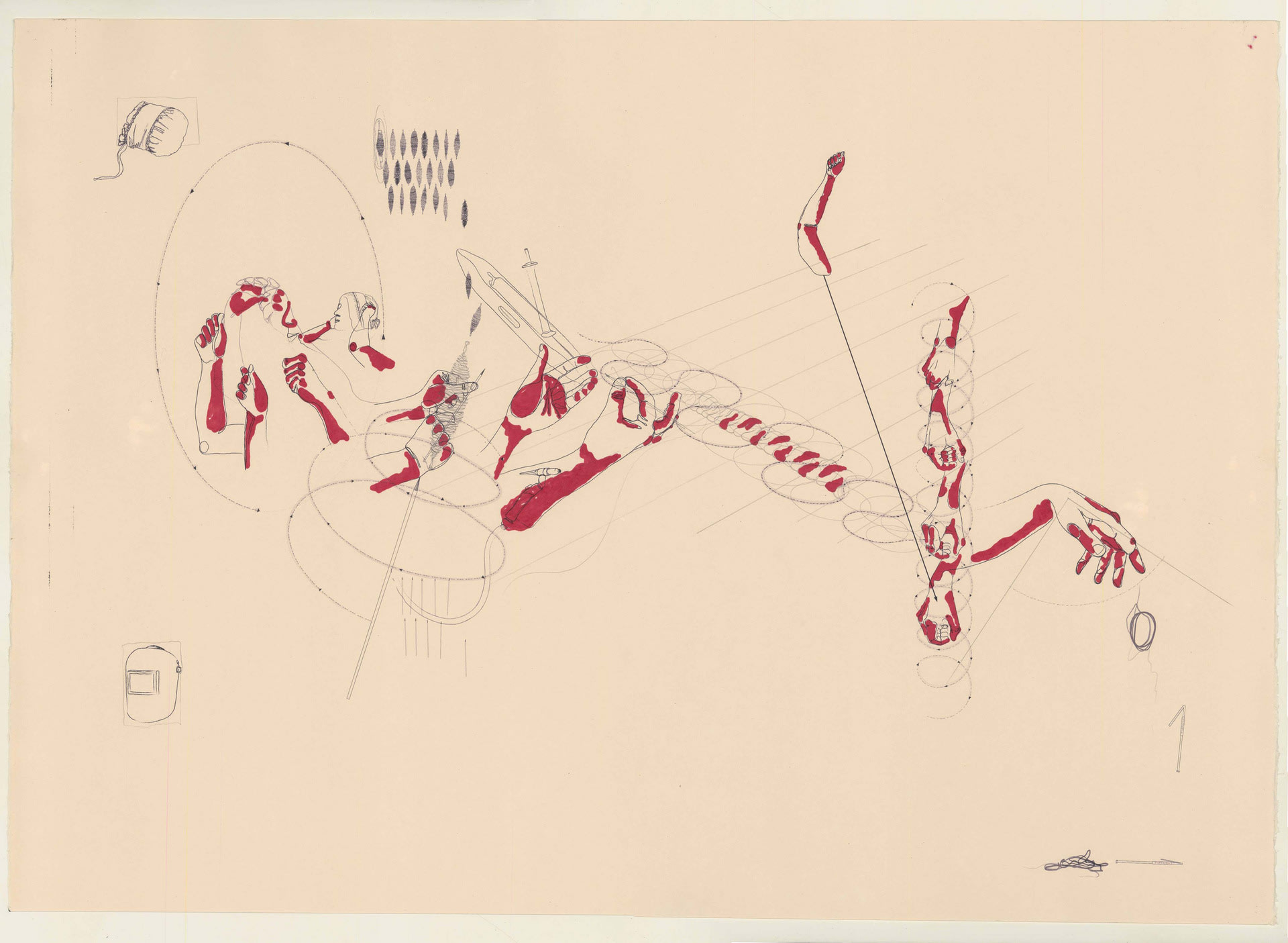

Having come from a background in manufacturing and fabrication, I have a particular interest in the workshop - both as a place of occupation, and as the space in which the wider components of our built environment originate.

Prior to studying at the RCA, I completed my BSc Architecture at The Bartlett School of Architecture in 2017, before working in the Stockholm office of the interdisciplinary practice, White Arkitekter. Since 2018 I have worked in fabrication workshops across the North West of England, London and Berlin.

I am very grateful to have been the recipient of both the Burberry Design Scholarship, and the Design Education Trust 4D Project Award during my studies.

Currently, I work in the London based design and fabrication studio Mitre and Mondays.